Fresh Eyes is a new column reassessing milestone stories in comic book history from a modern perspective. Do they hold up, and how might they resonate with today’s readers?

In the mid-1970s, the Black Panther starred in a sprawling 13-part epic called Panther’s Rage in the pages of Jungle Action by writer Don McGregor and artists Rich Buckler and Billy Graham. With promotion heating up for the 2018 Black Panther movie from Marvel Studios, it seemed like a good time to revisit this story. For me, it was the first time reading it.

HISTORY

The first black superhero, Black Panther, was created by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee in the pages of Fantastic Four in 1966. Before that, black representation in mainstream superhero comics was mainly relegated to cringe-worthy stereotypes cast primarily in the roles of comic relief and sidekicks. Playing against cultural expectations, Kirby and Lee presented Black Panther, or T’Challa, as a noble king of great intelligence, grace, and skill competently ruling a fictional African nation that was wealthy and technologically advanced. For probably the first time in American comic books, African culture was both embraced and emboldened by white creators.

Black Panther continued appearing in Fantastic Four for a few more months, and then next popped up as a guest star in the Captain America feature by Kirby and Lee in Tales of Suspense. This story launched a new Captain America series in 1968 by the same creative team, at which point Black Panther moved over to join the cast in Avengers by Roy Thomas and John Buscema. What seemed like a great promotion for the character ended up not doing much for him. With the rise of the Black Panther Party, an influential yet controversial black movement organization unrelated to T’Challa, Marvel seemed to back off promotion of the name and character, possibly out of fear of being accused of promoting the group. As such Black Panther only occasionally got the spotlight in Avengers, and subplots had him essentially abandon his country by becoming a school teacher in Harlem and dating a Gladys Knight-esque singer.

By 1972, Don McGregor was serving as proofreader for Marvel Comics and one of his assignments was a comic titled Jungle Action. This was a resurrected title of the same name from the 1950s. Its return was probably part of Marvel’s market saturation strategy at the time and maybe to keep rights to the title still alive. It contained reprints of jungle-themed stories from the ’50s. Despite their settings, these stories consistently starred an all-white cast of characters. Legend has it, McGregor complained about the dated nature of the stories he had to proofread, so Marvel gave him control of the series. He set out to create new stories that featured black characters and chose Black Panther as his focus. Perhaps to test the waters, a reprint of Avengers #62 from 1969, which had Black Panther in the spotlight, was used to transition the series. And then, in Jungle Action #6, a new solo tale starring Black Panther began. Of course to hedge their bets, Marvel still had a dated reprint of Lorna the Jungle Girl fill out the back half of the comic for the first two issues just in case they needed to abandon the idea.

Even so, after 7 years, Black Panther was finally headlining his own series. While exciting, he was not the first black superhero to get there. It was now 1973 and the Marvel Universe was finally starting to get just a bit more diverse. In 1971, Captain America had been retitled Captain America and the Falcon, co-starring the high-flying Sam Wilson. Then in 1972, a black character was given his own series for the first time, Luke Cage, Hero for Hire. And now, each issue of Jungle Action declared “featuring the Black Panther” in larger font than the book’s official title.

CRITIQUE

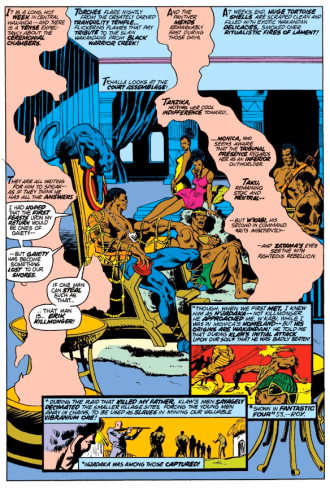

The only real mandate Marvel’s editors initially placed on McGregor was to set the stories in Africa since the comic was still technically called Jungle Action. This allowed McGregor to return Black Panther to his county, the fictional Wakanda, where its politics, its people, its culture, could be more deeply explored than had been done before. The advanced technology was juxtaposed against some of the more traditional and conservative people of Wakanda. Black Panther’s time in America with the Avengers was used as a direct cause of the country’s tension, where a coup was being attempted.

Perhaps most striking of all for American superhero comics of the time is the entirely all black cast. Unlike Captain America and Falcon and Luke Cage, Hero for Hire only one white character appears in the entire Panther’s Rage story, and he spends the majority of his time as a prisoner. It’s also distinct for being a Marvel superhero story not set in America, not even the superhero magnet New York City. The entire series, besides a brief flashback sequence, is set in Africa. This subconsciously reinforces the idea that these characters and their culture are enough. According to interviews, McGregor has said that he was pressured to have other Marvel heroes guest-star in the series to help boost sales, but he refused. The Avengers are only spotted once or twice in small, single-panel cameos. He probably knew how having Spider-Man swing through Wakanda would symbolically water down the immersive experience he was building.

Panther’s Rage is indeed an immersive experience. From the outset, McGregor plotted the story as a multi-part epic, similar in structure to old movie serials (although cliffhangers were abandoned early on). This results in a tightly written series where each scene builds on the themes and narrative crucial to that individual chapter, while driving to a single conclusion. This tunnel vision focus is enhanced by McGregor’s scripts, which featured intense narrations that add emotional layers to the visuals they accompany. It’s important to note that the script is additive, not repetitive to the visuals. The script provides information, but it’s not just there for factual information. It’s at times poetic and contemplative, reflecting the emotional state of the characters. It also expands on what is seen in a single panel, filling out what can be imagined happening between panels. Some mistake it for overly flowery or melodramatic, and too wordy. I found it refreshingly complex and dense for a newsstand-distributed comic book from the mid-’70s. This isn’t a light read, it deserves more attention, and with it you get a better experience.

The art reinforces this experience. The linework may look dated for today’s standards, but the visuals really flourish when experimenting with page layout and design. Interviews suggest that many of the layouts, particularly for the title pages, were conceived by McGregor for the artist to realize. Rich Buckler, a Marvel mainstay of the time, kicked off the series, allegedly at Buckler’s own insistence. Marvel would’ve prefered him to do something a bit more high profile, but he and McGregor were friends and Buckler apparently believed in the project and McGregor’s vision. Buckler was joined by a new inker just breaking into the comics industry, Klaus Janson, who would go on to collaborate with Frank Miller on definitive comics like Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. Gil Kane stepped in for an issue, and stayed on as cover artist, and then Billy Graham took over as the regular interior artist. Graham had just worked on the first 17 issues of Luke Cage’s comic series, usually as an inker but sometimes stepping in as penciler and co-plotter. As one of the few African-American artists working in comics at that time, his addition to the creative team added a crucial element of authenticity to the book. He’s also fantastic, expertly providing his own experimental layouts and designs conceived by McGregor. The epilogue featured Bill McLeod inking Graham and the two make a great pair.

The innovative title pages harkened back to Will Eisner’s classic 1940s comic The Spirit. In 1968, Jim Steranko resurrected the technique in Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. and Eisner himself would continue to explore this with his graphic novels. His first, A Contract with God, was still about 4-5 years away at the time Panther’s Rage began. In fact, A Contract with God is often credited as being the first graphic novel. While not truly correct, it certainly popularized the term “graphic novel.” McGregor himself would go on to create early graphic novels such as Sabre and Detectives, Inc. It’s perhaps fitting then that Panther’s Rage, created intentionally to exist as a whole, was only finally presented that way about 40 years later when Marvel began releasing graphic novel collections of these issues.

But a story without compelling characters is hardly worth it, no matter how ambitious. Fortunately, the story is populated with a number of characters that create a more rich world for Black Panther to explore.

The Gladys Knight knock-off, here described as a “second-rate Aretha Franklin” is Monica Lynne. She’s only one of two characters from America in the entire story. She is the part of Black Panther that the rest of the country is suspicious of accepting. She is an outsider who doesn’t respect or appreciate their traditions. More than just “Black Panther’s girlfriend,” she tries and often fails to connect with the people around her. She eventually helps an injured villager get to Wakanda’s modern hospital. She and T’Challa’s relationship is sweet and the two clearly respect each other.

T’Challa’s court is made up of W’Kabi, his second in command and head of court security. His friendship with T’Challa has been strained since the king’s return. He resents his king having been gone, and the strain this has taken on him is reflected in his disintegrating marriage. These scenes are made all the more heartbreaking in knowing that McGregor himself was going through a painful divorce during the making of these issues. Taku is the communications advisor, a gentle and more contemplative soul, who is able to open T’Challa’s eyes to how remiss he’s been in his absence. He also acts as guard and interrogator to the sole white character, a villain by the name of Venomm, and the two form an unlikely, begrudging friendship. (While not explicit on the page, McGregor has since stated his intent was that the two had formed a romantic relationship, but he felt it was too risky a reveal along with the book’s other controversial elements.)

Two recurring characters, Kazibe and Tayete, are two foot soldiers that have joined the insurrection forces. They provide some really well-balanced comic relief. They add levity to the story without breaking the tone and reality of the series, and allow us to see Black Panther develop a subtle sense of humor himself because of their repeated encounters.

The series sees a number of villains introduced, but they’re all connected back to Erik Killmonger, who is introduced in the first two issues. He is a massively imposing figure who is leading the insurrection and planning a coup to overthrow Black Panther as king of Wakanda. Killmonger easily overpowers Black Panther. Just when you think T’Challa will rally and win the upperhand, Killmonger again strikes him away. This illustrates one criticism I’ve seen this story get, which is that Black Panther never truly wins, and when he does, he wins due to someone else intervening. Some feel this makes him seem ineffective and less powerful. To me, this is not a weakness of the story, as one of the recurring themes is T’Challa’s persistence. The absolute force of will that he finds to get through some terrible situations with unfavorable odds has a long simmering, slow build. At times, he is dragging himself through the story, and in the end he does win because he is part of his community. He finally finds out he doesn’t have to do it alone, and in the epilogue, he and W’Kabi mend their friendship and work together to win the day. If Black Panther were a passive character in his own story, I would agree more with the criticism, but T’Challa is constantly taking the initiative to avenge the death of his countrymen and heal his country. Each issue he makes progress, but it is painful progress, and his navigation of that is compelling.

The layers, interweaving relationships and subplots, and the disciplined pacing and innovative layouts put Panther’s Rage head and shoulders above a lot of contemporary comics of the day. It is a natural predecessor to the eventual sophistication in craft that would be embraced in works like Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns, just as Mark Gruenwald’s Squadron Supreme is a natural predecessor in theme to Watchmen. Needless to say, I thoroughly enjoyed it, and it made me love Black Panther even more. Since these stories, the character has gotten tougher, sometimes compared to Batman in resourcefulness. These stories hold a lot of magic, passion, and intrigue that pay off for a reader looking for fun adventure with more depth.

HOW TO GET IT

The original issues were published from 1973 to 1975 and can still be found through many local comic book retailers here or here.

Marvel has released collected editions of the issues three times now, but not until this decade. In 2010, Marvel Masterworks: Black Panther Vol. 1 was released as part of their high-end hardcover series. Priced at $64.99 but now out of print, it included Jungle Action #6-24, which includes the entirety of the Panther’s Rage story, as well as the following story in the series. In 2012, Essential Black Panther Vol. 1 was released for $19.99 as part of their cheaper black and white softcover reprint series. Also now out of print, it included the same issues of Jungle Action as well as the first ten issues of Jack Kirby’s return to the character in 1977. And then last year, Marvel released Black Panther Epic Collection: Panther’s Rage, as part of their full color softcover Epic series of reprints. Priced at $34.99, it includes all the Black Panther-relevant issues from Jungle Action previously reprinted in the Marvel Masterworks edition plus the character’s first appearances in Fantastic Four #52 and 53. (This is what I used to read this story, and it includes wonderful bonus material such as McGregor’s script outlines, layout sketches by Buckler and Graham, photos and much more.) Also last year, Hachette Partworks released a collection of Jungle Action #6-18 as the 116th entry in their subscription-based Ultimate Graphic Novels Collection series for the UK and other countries overseas.

Or if you prefer digital, comiXology has Jungle Action #6 and 7 for $1.99 each, as well as both the above Epic Collection ($24.99) and Marvel Masterworks ($16.99) editions available. Surprisingly, they are not yet on Marvel’s all-you-can-eat digital comics subscription service, Marvel Unlimited.

Black Panther: Panther’s Rage

(originally published in Jungle Action #6-18)

Writer: Don McGregor

Artists: Rich Buckler (#6-8), Gil Kane (#9), and Billy Graham (#10-18)

Inkers: Klaus Janson (#6-12), P. Craig Russell (#13), Pablo Marcos (#14), Dan Green (#15), Billy Graham (#16-17), and Bob McLeod (#18)

Colorists: Glynis Wein (#6-12 and 14-16), Tom Palmer (#13), Michele Wolfman (#17), and Don Warfield (#18)

Letterers: Tom Orzechowski (#6-9), Dave Hunt (#10, 12 and 18), Artie Simek (#11), Joe Rosen (#13), Charlotte Jetter (#14 and 17), Karen Mantlo (#15), and Janice Chiang (#16)

Cover artists: Rich Buckler (#6-8 and 13), Gil Kane (#9-11 and 13-17), and Jack Kirby (#18)

Editors: Roy Thomas (#6-13), Len Wein (#14-17), and Marv Wolfman (#18)

https://www.facebook.com/artistbillygraham/ Billy was my grandfather 🙂