Maximilian Uriarte began making the comic strip Terminal Lance when he was still an active duty Marine. He continued making the strip while in art school and since. The strip has become a phenomenon, but Uriarte gained a larger audience with the publication of his 2016 graphic novel The White Donkey.

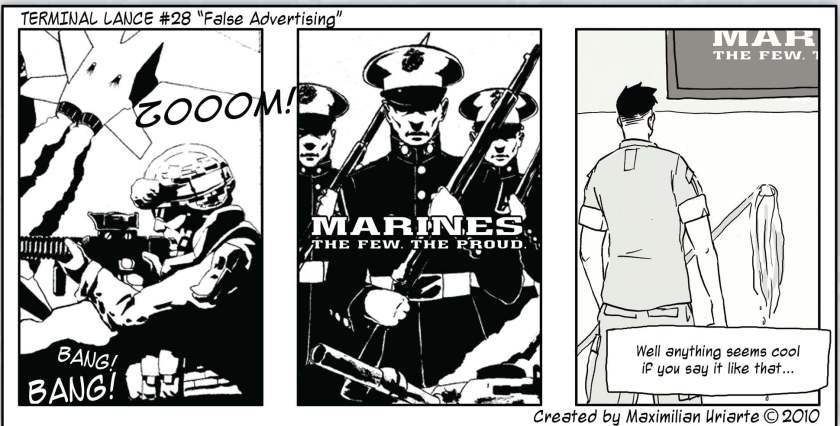

Little Brown has just released Terminal Lance: Ultimate Omnibus, which collects much of Uriarte’s strip along with notes and commentary. The strip skirts the brutal realism of The White Donkey and is instead strange and surreal, funny and weird. It’s easy to see why the strip became so popular. So often marines are portrayed in very one-dimensional ways, but what runs through all of Uriarte’s work is the desire to show them as human. This is not propaganda, this is not a recruitment tool; rather, in both the comic strip and the graphic novel, Uriarte seeks to be honest above all. Sometimes it’s funny or absurd, sometimes disturbing, sometimes brutal. I spoke with Uriarte about the strip and the collection.

You started Terminal Lance after your second deployment in Iraq, do I have that right?

Pretty much right after I came home from that second deployment. I came home in September ‘09 if I’m remembering correctly and Terminal Lance launched officially in January.

What happened during that deployment that made you go, “I should make a comic strip”?

What happened during that deployment that made you go, “I should make a comic strip”?

I felt like it was filling a void. I remember looking around and there was only this one comic strip about the Marine Corps that I knew about. It was called Semper Toons and it just wasn’t true to the Marine Corps that I knew. I wanted to get that other side of the Marine Corps out there – that this sucks – and make fun of it. I found it more representational of my actual experience.

You were still in uniform when you started the comic. How did it go over?

[laughs] It went over surprisingly well. I was still active duty when it came out and I was sure I was going to get in trouble, but it never came. I think people appreciated the honesty of the strip. The humor that the strip draws from is based in reality. Terminal Lance has never defamatory for the sake of being defamatory, it’s just been honest. At least I like to think so. I never got in trouble. I had to go I had to go talk to the base legal department to make sure I wasn’t breaking any Marine Corps orders. Which I wasn’t. But that was it. I only had a few months left so I think I got it out before they could slam the door. [laughs] I don’t think the Marine Corps would let it happen again, to be honest.

I ask because soldiers loved Bill Mauldin, today he’s a legend to so many, but Patton thought Mauldin was an anarchist and wanted to throw him in jail. Beetle Bailey was dropped from Stars and Stripes twice. Making Terminal Lance seems like asking for trouble.

I ask because soldiers loved Bill Mauldin, today he’s a legend to so many, but Patton thought Mauldin was an anarchist and wanted to throw him in jail. Beetle Bailey was dropped from Stars and Stripes twice. Making Terminal Lance seems like asking for trouble.

It is, yeah. It’s definitely a product of a modern social media age, too, where even if they somehow censor me, I feel like these opinions would be out there anyway. Social media culture has really taken over the military and it’s hard to censor people in the same way it used to be. I think social media has opened up a whole era of free speech.

I was going to say and some of this is because of when you were working on this, but Terminal Lance feels in some ways like an outgrowth of how we use social media and how we communicate through social media.

I would agree with that. Social media has paramount to Terminal Lance’s success. That was how I got the word out at first. I think it all goes hand in hand. There’s a lot to be said about social media culture within the military community and how it’s affected the military over the past eight years or so. I feel like Terminal Lance led the way in a lot of ways actually because it was like, are we allowed to say this? I went for it because no one said no. The Terminal Lance facebook page and instagram page are this weird insider glimpse of the Marine Corps.

You were working on The White Donkey and Terminal Lance at the same time for years and they are very different projects.

You were working on The White Donkey and Terminal Lance at the same time for years and they are very different projects.

They are very different. The White Donkey is a passion project that I really wanted to do. I think it’s very similar to Terminal Lance. I think it does the same thing that Terminal Lance does, which is be brutally honest with itself to the point where it’s like not nice to its own experiences. But doing it in an effort to learn from it and find meaning in it rather than shield yourself behind propaganda. I think The White Donkey is a brutally honest look at the Marine Corps experience and the experience of going to war in Iraq.

I kept thinking that Terminal Lance is about the Marine Corps and The White Donkey is about the war in Iraq. Which is simplifying both a lot.

The White Donkey isn’t really about Iraq. It’s about a marine and his experience in that environment. Iraq is part of that, obviously. But I wouldn’t say it’s about Iraq. Although it is. [laughs] It’s about the Marine Corps in the same way that Terminal Lance is about the Marine Corps, but it’s a very realistic and dramatic depiction. It’s also based a lot more on my own experiences. The comic strip is drawn from my own experiences too, but it’s obviously insane and crazy things happen. People turn into literal giant douche bags and there’s weird stuff going on all the time. I feel like they’re both the same root but different expressions of it. [The White Donkey] is really more about the experience of war. Combat is kinetic action whereas war itself is this long droning meandering thing. It’s really about experiences and expectations and disappointment and guilt.

But one theme in The White Donkey is how war can affect you in ways you don’t expect. And I worry about how I phrase that because there is a lot of stigma around PTSD and mental health issues – inside and outside the military.

But one theme in The White Donkey is how war can affect you in ways you don’t expect. And I worry about how I phrase that because there is a lot of stigma around PTSD and mental health issues – inside and outside the military.

Exactly and in The White Donkey I wanted to tackle those issues. I had two objectives with The White Donkey. One was for marines and the other was for civilians. For marines I wanted to show them their own experience and I wanted them to identify with it. I feel like if you see someone else go through it, it might inspire you to get help or maybe it just helps you get perspective on your own experience. I’ve gotten so many e-mails from people who said, I read your book and I didn’t realize all the things I was struggling with until I saw it in front of me. Which makes me feel really good that marines can identify with it. For civilians I wanted to show them from the beginning how a marine could get to that point and show them what this is like and how it feels and be honest about that. People always say, civilians don’t understand, but I feel like they can. They just have to experience it.

The military can be this closed culture and there is often this fatalistic, you’ll never understand attitude towards civilians.

You always read about the military-civilian divide and there’s a lot of veterans who feel like the onus of it is on the civilians to come to them. In my opinion I feel like service members had these experiences that are different from a normal life and it’s really up to us to bring this experience back and tell people how it was. We’re the ones who had this crazy experience. I think a lot of veterans close themselves off from doing that and I think that doesn’t help.

Anyone who flips through the collection can see that your style has changed over the years. You mention in the book that you started working on paper initially. Why did you decide to work digitally?

Anyone who flips through the collection can see that your style has changed over the years. You mention in the book that you started working on paper initially. Why did you decide to work digitally?

It was practical. [laughs] There’s no deeper explanation. I did the first thirty-five strips, I think, by hand on bristol with ink. I would scan them into the computer and add the text and everything. I got out of the Marines and I lived with my mom for the summer until the school year started. In the meantime I didn’t have a work desk or anything but I had a wacom tablet so I just drew them straight onto the computer and never went back to doing them on paper. It was like I cut out the middle man by not having to scan them in. Doing it that way saved a lot of time. I switched to a cintiq monitor after The White Donkey came out and that really informed the artwork, too. The other thing that I was doing was developing a lot of animation for various other purposes that were unrelated. I was working with these styles that needed to be animated and so it made me think a lot more about how to simplify the shapes and forms. The comic has gone through a lot of evolutions, but I think it’s at a pretty good place right now.

In art school were you studying animation?

I went to California College of the Arts in Oakland. I started out as an illustration major but then I met a friend in the animation program and I got really into that so I transferred to the animation department and I just loved it.

You’ve mentioned in other interviews that you’re working on another book. I don’t know where you are in the process, but do you want to say anything about it?

I can’t say too much about it but it is called Battle Born. Other than that I can’t tell you much. It’s about marines in Afghanistan. I’m excited about it because it’s departure from Terminal Lance. Even though it is about the Marine Corps and Marines. I’m really excited about it. I haven’t officially announced it but I’ve hinted about it here and there.

It feels as though a lot of how we understand the War in Iraq has been through personal narratives. What do you think we gain and what do you think we miss by seeing things through that lens?

It feels as though a lot of how we understand the War in Iraq has been through personal narratives. What do you think we gain and what do you think we miss by seeing things through that lens?

I think we gain reality. I feel like learning about a war in a strictly factual historical context takes away the humanity from it and war is all about humans. It’s about humans killing other humans. It can be a traumatic experience. I think the only way to move away from war is to understand the human toll that it has. Traditionally people have always thought of military members as being very inhuman. My goal has always been to humanize marines. They’re people who get caught up in these extreme circumstances and they are not robots or whatever people think military people are. I think humanizing that experience is really important for everybody.

I ask that question for the obvious reason, but also a while back on the website you were talking about how you loved the movie Jarhead and how cool you thought it would be to be a Marine sniper – and how you kind of missed the point of the movie. That’s a criticism made about a lot of narratives about the military and war.

Marines are split on that movie. People like me love it because we feel like it’s a very accurate realistic depiction of how shitty it is and how true to life it is. Others are motivators who think Anthony Swofford is just a whiner. You can always tell who’s an asshole and who’s not from whether or not they liked Jarhead. [laughs] I think it’s a great movie because it’s honest. It comes down to, is it depicting this experience accurately? It’s funny because I get the same sort of reaction about Terminal Lance. I think Terminal Lance is being honest. Do you appreciate that honesty or do you despise that honesty? I think that a lot of people who don’t like Terminal Lance or Jarhead are afraid of confronting their own reality that maybe this experience sucks. [laughs] There’s a lot of hoo-ah propaganda about how the Marine Corps is this infallible thing that’s existed since 1775. These works challenge that whole narrative. It’s not vindictive, it’s just being honest. This was my experience. It’s funny because people think because I do Terminal Lance and I’m still really involved with the Marine Corps community that I’m some kind of motivator. I get emails all the time that are, I’m shipping off to boot camp next week do you have any advice for me? Every single time I get asked this question I say the same thing: Don’t go. [laughs] Stay home. I don’t pull my punches. I remember reading some comments on the facebook page about how these comics were the reason I enlisted. I was like, I think you’re reading the comics wrong. [laughs]