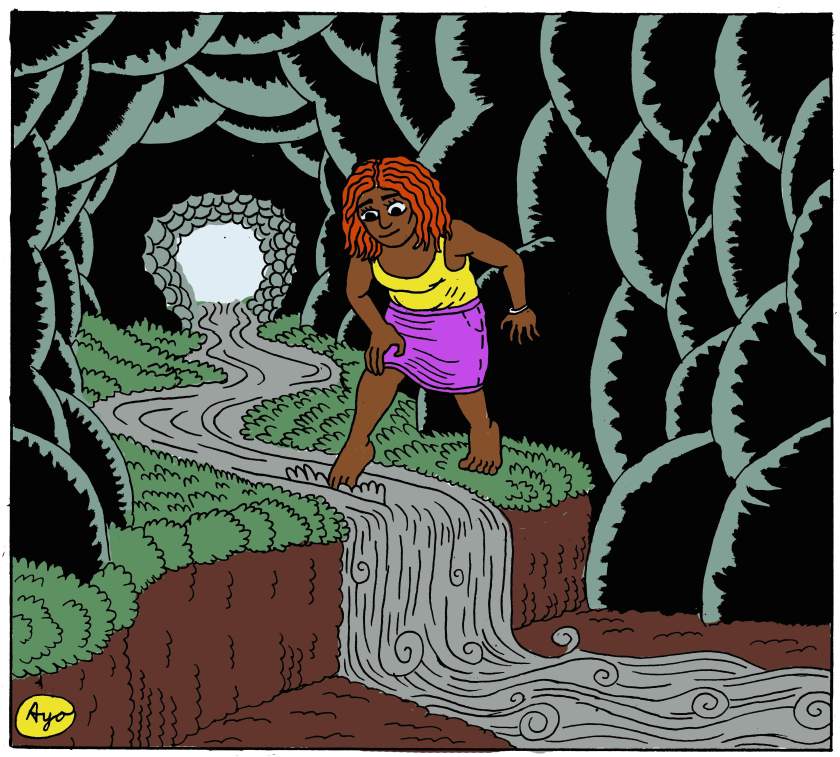

Darryl Ayo has been making comics for years and remains known today for not just his comics, including the series Little Garden, but for his criticism. He has been published in The Comics Journal, Comixcube, Comics MNT, The Hooded Utilitarian and elsewhere. Little Garden features mythological creatures and humans in a world that is clearly not ours, but the focus of the series is centered around more mundane events and interactions. It also possesses Darryl’s sense of humor and a great sense of design and composition.

Ayo and I have met at shows for years and we’ve interacted on Twitter, but we’ve never before sat down to talk in a formal interview. So we took the opportunity to chat about his work and process.

How did you first come to comics?

I remember that pretty clearly. When I was very little and my mom called me over and showed me the Sunday paper with Calvin and Hobbes in it. She read it out loud. I can still describe it. It was where Calvin and Hobbes go to the beach and the sand is too hot and the water is too cold so they’re going “oh oh eh eh” across the sand and then “brrrr” when they get into the water. They keep going back and forth. That’s the strip. That was my first exposure to comics. This was the 80s and early 90s and comics were still around in the culture. I got into the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles spinoff for Archie and then X-Men. I felt stalked by the X-Men as a kid. My first exposure was the Saturday morning cartoon. I caught the pilot, The Pryde of the X-Men, and then I saw the NES video game. Eventually I realized oh this is a whole thing and everybody likes it. I started reading those and I latched onto them for a huge part of the 90s. I thought, I’d like to do this growing up. That was the age I was at where you have to start gearing yourself towards the future and adulthood and I thought, I like comics?

One thing that is interesting is that you’re reading and writing about superhero comics, but seem to have no interest in ever making them or anything like them.

Well, I was not into superhero comics after 1997. I was reading Spawn because you had Greg Capullo drawing them and he’s really cool. I liked him from his work on X-Force. Spawn was cool because it was a self-contained comic and it was very episodic. I didn’t feel the manipulation of dragging things out. Each issue was another Spawn adventure. There were a lot of comic stores in Westchester county and there was a comic store that I had been to, but I did not habitually go to. This comic store sold manga. Which came out in single issue form. And that was it. The new issue of Spawn was out and I looked at it and said, it’s over. I dropped Spawn. X-Men were terrible in ’97. All that stuff just went right away. I was done with it overnight. Easiest breakup of my life. [laughs] I grew up with the superheroes and I ditched them when I realized that something more my actual taste came out. I latched onto that.

So I’m out of superheroes and manga by the time I go to college in ’99. In college I was trying to find artsy graphic novels and the graphic novel boom hadn’t started yet, but you had Fantagraphics, Drawn and Quarterly. Superheroes just didn’t seem interesting in that light, even though that was around when a lot of interesting things were starting to happen like New X-Men and X-Force/X-Statix. I took a look at them. Much later, adulthood and working a day job and depression – and it hit me one day that the only thing I want to be interested in is a comic that I had always described in this way in my head: A comic where the problem is solved by Thor smacking something with a hammer. Adulthood is bad and I just wanted something simple but dependable. I started to get into superheroes in my late 20s, early 30s as this sort of midweek break. Comic books come out on Wednesdays and work is awful and life as an adult is brutal and so in the middle of the week you get this boost. You’ve got to be into superhero comics for that. It was very much, I think these things are beneath me but I really need something dumb to look at. I got into them but by then I was already a completely through and through alternative comics person. It’s more like how some people might be into important film but they also love watching reality television.

You mentioned that you wanted to make comics when you were a kid. At what point did you start making them?

I think it’s much more difficult than a person thinks to make comics. I tried doing a couple of comics in high school, but I didn’t make comics consistently until I was in art school. Everything is in these bursts for me. The illustration studio was on the top floor of the building and I thought of this comic mid step. I pulled out my sketchbook and started drawing this comic. I did it all that night. I did the same thing the next day, the day after. I drew a one page comic every day for a while. Scott McCloud put out his book – the one everyone hates – Reinventing Comics. Everybody hates it but he made it in this depression that the comic book industry in America is going down the tubes and we don’t know what to do, but he’s a believer. He believes in comics. He has this passage about what if there was a storefront with full size reproductions of the pages and you could turn the pages on the sidewalk. I was reading this thinking, why don’t you just make the comic fit on one page? What I like to tell people is that I essentially invented comic strips. [laughs] Why not just make the comic on one sheet so that when people see the comic, they see it. We didn’t have comics at my school, we had illustration, so I was around a lot of people who were interested in drawing but weren’t necessarily interested in comics. I knew a guy who went onto be a really successful artist and he was doing gig posters when we were in school. I was around this type of energy and I thought, why not make a comic like a poster? It took me a few years to realize, that’s a comic strip. But I started coming up with ideas for one page comics. I would make them in my 9” x 12” sketchbook. I was making them every day until I burned myself out. That was where I got my real start and started making minicomics.

Even now Little Garden is an ongoing comic, but you make them mostly one page or one short comic at a time.

That’s true. There’s a lot of cyclical learning in my life where there’s something that’s really important and then I get away from it and have to rediscover it later. No one can tell you what to do, you have to discover it on your own. A little history on Little Garden, I started drawing a short comic back in college and never finished it. I graduated college and I was at home, had an art degree, don’t know what I’m doing with my life. I’m walking up the stairs and I said to myself, I’m going to draw something tomorrow. It’s going to be the easiest thing in the world and it’s going to be something that I do every day. I took my sketchbook the next day and started drawing and that was the beginning of Little Garden. It was an illustration of this character I had previously created in a scene. The next day I did it again. I got an almost identical sketchbook when that one was completed. I maintained that from 2004 to 2007. It was a little inconsistent in the second half of that. When I started I was just out of college and I didn’t have a job. Doing it every day made me feel very accomplished, but it was disjointed. It was whatever I thought of at that moment. It wasn’t a story but it had a cohesive set of aesthetics to it. It seemed story-like because of that, but really I didn’t want to challenge myself in the traditional way. The big challenge was, can I keep making this?

I hedged everything towards what is easy for me. Natural forms, not geometric built structures, so grass, trees, bushes, fruit, rivers, streams, rocks. Something that I could really depend on for myself so that I could make it as likely as possible that I would continue making more and I think it worked because I got pretty far in that before I got too far away from it and I was deep into working and wasn’t devoting enough of my emotional energy to it so I lost track of it. I tried throughout the years for a good ten years to find another way. I got into drawing single page comic strips again and then at some point I did these medium length 20 page stories. I don’t know when Little Garden turned into one page comics officially but it was this good compromise to bring me back into that rhythmic pace of doing a short burst every day and then but also having the narrative elements that I’d introduced. The speed of my youth isn’t there anymore and I’ve been a little bit too concerned with what had been built up. You start something fresh and you can do anything because anything makes sense – because you haven’t established much. But once you establish stuff, all you feel are the restrictions of what you can’t do. I wasn’t able to think of ideas as quickly as I thought I would because all I could think of were the boundaries of what I’d established.

You mentioned not having the same speed and I was curious whether that was writing or drawing, but it sounds like you’ve changed a lot about how you work over the years.

It’s all about writing. I don’t even know how to draw slowly. I really came into everything about art based on comics and all I knew about comics is that they’re out all the time so you clearly have to be fast, so I never learned how to be slow at drawing. Once it gets to the point where I can draw, it’s out there. It is really is the ideas, the writing. And by writing I not just the literal words. I think often the literal words are the easiest part. You build up this framework and then you improvise on top of that framework. The framework is the idea of the story and the improvisation is the script. One person says this, another person responds. I think the benefit of Little Garden comic is that when I established it in the beginning, the illustrations didn’t often have a discernible point. They were often just vignettes. A lot of the times the strips aren’t meant to be funny or even important. Just, here’s a sequence of events in these people’s lives. It’s just a little moment in time. I don’t have to turn it into a punchline. Sometimes they do turn out funny and sometimes they don’t. Like life is sometimes this hilarious thing and sometimes it’s just about hanging out with your friend.

The one page strip was also a function of the internet in general. Tumblr is pretty bad these days but back in its heyday – which is every time before this past December – you could put anything on Tumblr and it was like putting a ball on top of a hill and it rolls down the hill wherever it’s going to go, it hits whatever its going to hit, and reach whoever its going to reach. That was what was so great about it. Going back to the Scott McCloud, if it’s just there in one image, then whoever sees it, they get the whole point. You put the whole thing in one unit. You make a comic, make the website a Tumblr, and if it goes somewhere it can ricochet around the internet for as long as it can. Of course you don’t want it to ricochet aimlessly, so you put your links on it before you toss it out into the world. Maybe people think it’s funny, maybe they think it’s cute, maybe they think its weird, and maybe they click on the Patreon link and maybe they send a dollar. That’s the intention and hope. It kind of works but I wasn’t fast enough or aggressive enough to build it in the way that a lot of other strips do. I really believe in the mechanics of it.

Making a four panel strip where it’s not about punchline but just capturing this moment is something that comics does well. Frank King was the master of this, I think, where it wasn’t about punchlines, but just capturing a moment.

I would agree with that a lot. We’re talking about this after a lot of big internet comic strip people like Kate Beaton and Noelle Stevenson and a few others made these small bits of comics that could be absorbed by people anywhere. I think there’s often, I don’t want to say dismissiveness, but there’s a non-consideration of comic strips in the comic book world. They think of it as a different animal – and it is a different species. If you are determined to make a comic book, that’s fine, but if you just like comics, the comic strip has a lot to offer. I’m always asking people, what’s the function of comics? The original function of comic strips was to sell newspapers. Why would I buy your newspaper? This one has all the same news this one has and it has this cool comic. They wanted a guarantee that you would come back and read my newspaper every day. All of this comes out of a technical, structural need. I think a lot of people forget that. I’m always thinking about who is the person on the other end of this. Not individually, but what kind of life leads you to like a comic.

One of the things I think about a lot are, what are the good comics for the bathroom? I used to live with a bunch of roommates and I walked into the bathroom and there was a Calvin and Hobbes book. I get it. They’re short and you’re not going to be in the bathroom long enough – hopefully – to be reading chapters of books. [laughs] You don’t need a bookmark, you just open to whatever page and you read that and then go about your life. There’s this whole industry of bathroom books. It’s literally the humor section of the Barnes and Noble bookstore. You know what else is in there? Comics. Fox Trot and Peanuts collections. But graphic novels are over there in another part of the store. How does it fit into your lifestyle? I want to make a good comic. I like drawing single image illustrations and I enjoy comics. If I’m going to marry them, I want to make it efficient. I want to make it work for the person on the other end. If you have a book of strips from me then you probably would just take them to the bathroom. Those people who make the books in your bathroom are in your life so much more than the people who are considered the great authors. I think that’s good. I’m always experimenting with reading comics. I try different things to get the most out of comics.

That’s a good point. I was going to ask about how you think that people read Little Garden on the web versus as minicomics and it sounds like you’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how people read.

That’s really important. I’ve been worried about minicomics as a culture my entire adulthood. Ever since I encountered minicomics. It worries me because I don’t know what they’re for. I know what a superhero comic is for. You go to the store on Wednesday and you get your superhero comics and maybe you sit in your favorite chair or you go to your favorite coffee shop to read them. There’s also a culture of feedback around it. Culture is very important to me. It matters what groups of people do – and how that informs the art and how the art informs it. The thing about minicomics is that I can’t get a sense of the culture even being in it. I was looking around and trying to figure out who reads these. The answer is often, other minicomics people. That’s a broke person answer, first of all, and second of all, I don’t want to believe that.

There are differences between minicomics and traditionally printed comics like production values and things like that. Structurally there’s uniformity. Minicomics does not have that partially because minicomics can be any shape but that’s not the main reason. The main reason is that there aren’t enough people organized about it. If we all agree that we like minicomics and they’re important then first of all, how do we deal with them, and then who are we talking to? Are we just talking to each other? Because a lot of us are just talking to each other. But also who potentially could be doing this and what would their lives be like? One answer that I get to the question of who reads minicomics besides other cartoonists is other artists. That works for me as a starting point because it’s kind of a specialized item, so who are the people who want to deal with such a thing? Some people are making a graphic novel and they’re offsetting the cost of production by selling each chapter as minicomics which subsidizes its own publication plus keeps themselves in the public eye. So it’s loss leader for the final product and also engaging with the community. I get that. But is there an actual minicomics culture on its own? And if so, how are we doing it? I think it’s obvious, but it’s also difficult to articulate. Everybody complains about the lack of money but I’m always asking, how do we get to other people so there will be more money? Or just so we have a bigger audience and more people to talk to instead of just making things for each other? I want to advocate in the future for comics culture with an actual set of suggestions of how to promote comics. To tell people who don’t read comics, this is how you might read a comic. This is how it might fit into one’s life.

That’s one of the things we never talk about. My parents have read comic strips all their lives, and still do, but if I gave them From Hell and said there’s a great chapter about Christopher Wren and the rebuilding of the city after the Great Fire and what it means, they would look at me like I was insane. You’re laughing because you know what I mean. They know comics and know the language of comics and like them, but there’s something about approaching something longer than a strip.

There are certain mediums that are not good vehicles for information. One of my frustrations is the whole pivot to video. I don’t understand it because I read either slowly or very quickly, so I often do not want to watch a video where I am trapped in this other person’s time constraints and how long they want to take to explain it. I want to scan for key words and troubleshoot my problem from the middle of your article. Not watch this 16 minute thing. From Hell is a very good example because Eddie Campbell’s handwriting is this idiosyncratic thing. Nobody would say, this is how to letter comics.[laughs] It’s so good that you brought up From Hell because I remember reading From Hell. It was a long book! It was a long dense book and I wasn’t ready for it. It’s funny because Alan Moore is known for two things, Watchmen and From Hell, and one of them is super-clear and super-accessible and the other is the opposite.

So what are you working on now? Or thinking about next?

I’m trying to get into social commentary comics and political comics. I use Twitter a lot to talk about stuff and Twitter is fun, but I could actually turn this into something more permanent. I was never that interested in political comics, but I happened across some old Doonesbury collection. I was born in 1981 and so there’s a lot about the later 20th Century that I have no idea of, but here’s this day by day chronicle of what Americans were concerned about and yelling about throughout the mid-70s to the present. I’m learning stuff by having it laid out in this day by day format. I talk about politics enough that maybe it would be more productive as a cartoonist to get it out in comics form. I’m in this long process of retraining my brain to avoid blurting things out on Twitter, but instead sticking them in notes or in my notepad to deploy later.

Additionally, I have just created a new comic. It’s brand new and I can’t really talk about it, but it’s something that I’ve been trying to create. Little Garden was created from this general aspiration to make a comic book. When I started Little Garden I came up with this analogy that Little Garden feels invasive. This thing came into my life and took over my life and this is a small version of what it’s like to suddenly have a child. I didn’t feel like Little Garden was something I was doing so much as piloting or not even that. Raising it? Letting it develop where it wanted to be? It felt apart from me. I’m sure that anybody who has kids is like, it is not at all like that. [laughs] Little Garden is something that I love, but it isn’t me. I’d like to do some stuff that’s more of me, but I also feel this responsibility to shepherd and steward this thing that I’ve created so it’s always a mix. I always want to do Little Garden but I’m trying to develop a way to work on some things that feel more directly from my personality. It’s hard, but I’m brewing up some new stuff that could be interesting.