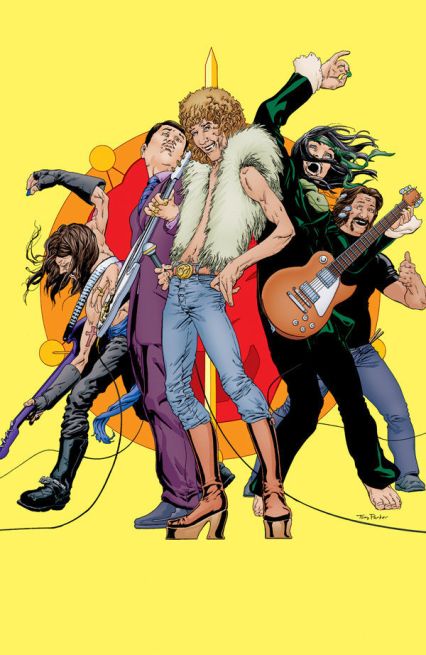

To say writer Paul Cornell executed the modern day equivalent of Jimi Hendrix setting a guitar on fire with his new creator-owned miniseries This Damned Band is an understatement. Cornell has teamed with artist Tony Parker and colorist Lovern Kindzierski on this one-of-a-kind mockumentary 1970s era period piece where a rock and roll band which acts like they worship the devil–only to realize they really do.

Thanks to Cornell for chatting with me about this Dark Horse published six-issue miniseries. Issue #1 was released on August 5, while issue #2 comes out on September 2. Part of me hopes to chat with Cornell after the miniseries wraps to find out more in terms of the Bowie and the Kinks anecdotes.

Tim O’Shea: Which came first the idea to tackle the 1960s/1970s era of music or the storytelling device do it as a mockumentary?

Paul Cornell: I think the band encountering the occult for real was the first thought, and the mockumentary style just felt like a good way to do that.

I don’t want you to spoil the story but am I right in thinking despite the death of Robert Starkey he plays a role of some kind in this miniseries?

It’s indicative of something, but it’s not going to be referred to in the strip. By the time we get to the end, I think readers will have gotten something extra out of it.

Continue reading “Smash Pages Q&A: Paul Cornell on Creator-Owned ‘This Damned Band’ from Dark Horse”