Welcome to What Are You Reading?, our weekly look at what the Smash Pages crew has been reading lately. In this week’s edition, we take a look back at Rick Remender’s opening salvo on Uncanny X-Force and the first Batman collaboration between Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams, among other comics. You can play along in the comments if you’d like.

Now here we go …

Tom Bondurant

The Batman makeover of the late 1960s didn’t start with Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams, but they staked out some pretty distinctive territory with their first Bat-collaboration — “The Secret Of The Waiting Graves!” in January 1970’s Detective Comics #395. “Waiting Graves” is kind of an atypical Batman story, and maybe not the one with which you’d expect a fifty-year tonal shift to start. It takes place entirely away from Gotham City, on a sprawling estate in Mexico. Its villains aren’t recognizable Bat-foes, but a married couple who have used magical plants to give themselves eternal life. They’ve invited Bruce Wayne and other one-percenters to a party in their family graveyard (!), and Batman ends up saving a guest from a balloon accident before running afoul of a couple of wolves, a pair of trained falcons and some hired goons. Turns out the cops view Mr. and Mrs. Muerto as drug dealers, so they’ve been trying to kill the government agent investigating them.

There’s not much inherently “Batman” about this story. With a couple of tweaks, the Muertos could have been foiled by James Bond, the Shadow or Zorro. Accordingly, it’s the style of the work which makes the most impact, and particularly its EC-esque ending. Seeing that Batman has set fire to their precious garden, the Muertos race to stop him, but in so doing their exertion “cancels the effect of the flowers’ fumes.” As their anxiety builds, the Muertos grow slower, older, and frailer, until they fall literally into their own open graves. The final panels show Batman standing over the headstones, and marking in “1969” for each date of death.

It’s a pretty stark contrast to the previous issue’s lead story, written by Frank Robbins and drawn by Bob Brown and Joe Giella, involving a Native American race-car driver who starts out wanting revenge on Bruce Wayne. With “Waiting Graves,” O’Neil and Adams were announcing that not only would Batman be spooky with a capital OO, his adventures would look more cinematic (for lack of a better term) than Carmine Infantino and company had established with the 1964 makeover. Although “Waiting Graves” featured a typical Adams “psychedelic freakout” panel, his realistic figures (and inker Dick Giordano’s careful lines) — plus O’Neil’s suspenseful script — sold the story’s fantastic elements. While “Waiting Graves” isn’t perfect (why were those graves open like that to begin with?) it’s not riding on its plot. Instead, it’s setting a tone, and ever since, the Bat-books have followed suit.

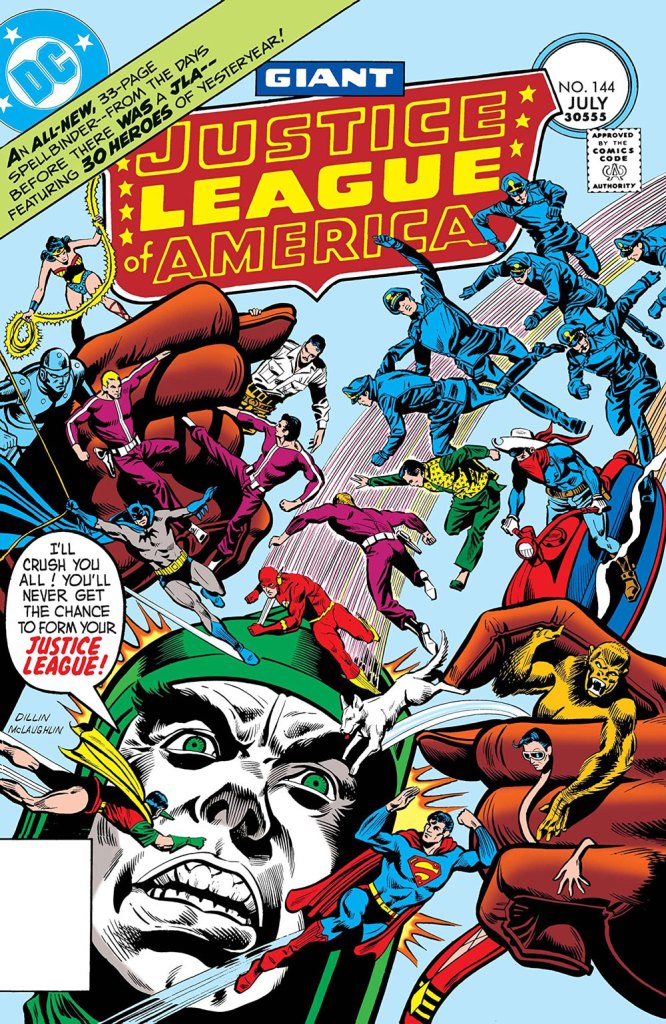

I also re-read one of my favorite Justice League stories, but this week it was with new eyes. “The Origin Of The Justice League – Minus One!” from July 1977’s Justice League of America issue #144 was written by Steve Englehart, pencilled by Dick Dillin, and inked by Frank McLaughlin. Its basic conceit is that all comics came out in “real time,” but it’s based on a continuity flub. Specifically, Green Arrow wants to know why the JLA considers itself to have started in February 1959 (three years before the origin was revealed in February 1962’s JLA issue #9), when Hal Jordan didn’t become Green Lantern until seven months later (September 1959’s Showcase #22). The answer involves a deep dive into League lore, as Englehart weaves a tapestry of references to craft a picture of paranoid Jet Age America.

Basically, in February 1959, J’Onn J’Onzz’s White Martian enemies have tracked him to Earth in order to kill him. In their pursuit, they feed the public’s fear of … well, UFOs, Communists, juvenile delinquents, you name it; and when J’Onn is himself exposed as a not-so-little green man, the nameless white folk of his adopted hometown are not having it. Fortunately, the Flash shows up to save J’Onn and provide a cooler head (although he gets a “how do we know you’re not Martian too?”). Realizing he’s out of his depth, though, he goes to Metropolis to call out Superman, and gets Batman and Robin as a bonus. The four of them then decide to alert all of DC’s late-1950s headliners, including the Blackhawks, the Challengers of the Unknown, Lois Lane and Jimmy Olsen, Congo Bill and Congorilla, Roy Raymond (TV Detective), Rex the Wonder Dog, Plastic Man, the original Robotman and Vigilante, and of course Aquaman and Wonder Woman. In true JLA fashion, they split into three groups, allowing Englehart and Dillin to have fun with the pairings. Not surprisingly, the future Leaguers end up on the same team, stopping the White Martians from riding a rocket back to Mars with J’Onn in tow.

Now, here’s where things got real for me. When all is said and done, J’Onn realizes he can’t go home. “The Mars I loved is gone! It is a world of lost causes and dead dreams! … But here, on Earth, the eternal struggle continues!” Superman is sympathetic, but the Flash worries there’s too much “hysteria” for J’Onn to go public. Aquaman muses that things could change in six months, and Wonder Woman says “when he does announce himself, it could be with the backing of all of us!” At that point I realized that these white superheroes had realized their privilege and were using it to help a new friend overcome the ingrained prejudices that society had put upon him. I don’t want to make too much of this – it’s not that Steve Englehart suddenly got woke, or that JLA #144 secretly represents 2020 attitudes on race relations – but in some small way it made me examine my own white privilege, and I’m grateful for that.

Carla Hoffman

When going through a ridiculously large comic book collection, you can often find yourself asking, “Why did I buy this?” Sometimes it’s a single one-shot issue that’s out of your usual oeuvre, sometimes it’s a mini-series that ends abruptly, sometimes it’s a whole run of books that you feel really meant something, but that was years ago. Why did I buy this?

So I stopped my endless categorizing and dug into about 20 issues of Uncanny X-Force from 2010, written by Rick Remender with art from such luminaries as Jerome Opeña, Rafael Albuquerque and Phil Noto. This comes from the polarizing time of the last remaining mutants, who gathered in a sanctuary in San Francisco and created their own Utopia. X-Force, being made up of a bunch of dangerous, morally gray X-Men like Psylocke, Wolverine and Fantomex, comes together to operate outside of Cyclops’ purview to do all the dirty work that a team like X-Force comes to do.

If you read the X-Men, you know the drill: these are the guys who shoot guns, have swords, will kill and face off against the edgiest of villains who have the darkest of motives. What really caught my eye back in 2010 and now nearly 10 years later is how that violence is handled and the context it is given from multiple points of view. Sure, you’ll see a gnarly decapitation or hail of gunfire, but the members of the team do stop to acknowledge that yes, they just cut that man’s head off and why they felt that was the only option. Big moral choices are made with reflective debate to follow after, trying to understand their choices and whether or not the greater good was served. Is it right for Psylocke to enjoy taking bloody revenge? Is Wolverine willing to put aside his own personal honor to serve the greater good? Can anyone trust each other when they all know how much blood they have on their hands?

Most of the first few issues deal a lot with Apocalypse and the legacy he consistently perpetuates. Can that kind of evil ever be defeated? Will we always be facing this ultimate destruction as the dark side of our constant struggle for peace? Can you even find hope when this is the same threat, over and over again? Yeah. It’s been kind of relevant recently.

The art is fantastic and really sold these kinds of moral grey areas with a raw, rough sketch on the page. Nothing feels truly finished, there are little to no defined dark black lines to tell you where the edges are. Everything is morally grey, including the art, giving it this very visceral and dream-like quality; despite a changing roster of artists and colorists, the style remains remarkably the same. As the characters stop and contemplate their lot in life and beyond, you the reader can stop and reflect on the very artistic masterpiece of a man’s brains being liquefied by beetles. If it was grittier or more “realistic,” I don’t think the book would work as well and could easily become another spectacle of hack and slash. Here in Uncanny X-Force, we have a solemn duty to really think and watch this horror unfold and make our own choices.

Yeah, I’m keeping these issues. If you’re looking for big X-Action with a bunch of grand designs on morality, violence and the evil that gods and men do, take a read through Uncanny X-Force vol.1.

JK Parkin

The most fun I had in comics form this week was Adventureman! #1, by Matt Fraction, Terry Dodson and Rachel Dodson. I loved the retro-futuristic world that the creators built here to introduce us to Adventureman and all his pals, as they begin setting up the next phase of the story, featuring the lovely Claire and her son Tommy. The Dodsons are in top form, esp. in bringing all the past characters and their battle to life.

Speaking of action, I enjoyed Daredevil #20 on several levels, as Matt Murdock’s latest crisis of conscience and character came to a head. But I especially wanted to call out the work of Marco Checchetto and Mattia Iacono on this issue. There’s a lot going on in this epic battle between Daredevil and his allies vs. Bullseye, Rhino and the other villains invading Hell’s Kitchen, and Checchetto and Iacono brought it to life superbly. I know choreographing fight scenes is a pretty standard task for many superhero comic artists; sometimes they work, sometimes they don’t, and fans are quick to call out the latter. So I wanted to make sure to recognize the former, in this case.