Ally Shwed is the writer and artist behind Fault Lines in the Constitution, the second book in the World Citizen Comics publishing line at First Second Books. Originally a text book written by Cynthia Levinson and Sanford Levinson, the book takes a look at how the United States Constitution was drafted, the debates behind its writing, and how those arguments and decisions continue to reverberate today.

People might know Shwed for her work on The Nib, where she’s written and drawn a number of excellent pieces, or for her work as one half of Little Red Bird Press where she’s edited two anthologies, Blocked and the recent Votes for Women. We spoke recently about illustrating abstract concepts, the struggle to craft a style that looks easy and what we can learn from what the suffrage movement did during a pandemic.

To start, how did you come to comics?

I was teaching high school literature. Not working in comics – and not drawing and not doing anything art-related – and one summer I went to CCS in Vermont. I did a weeklong workshop there and at the end of the week I fell in love with comics. A friend of mine had said, you might be good at comics and I went to workshop with the intention of finding artists to network with and work with, and by the end of the week I was like, I love this. I hadn’t drawn since I was a kid and so many people say, don’t go to art school, it’s not worth it, but I’m probably the one person who needed art school. I went to SCAD for their two year graduate program.

Did you want to make nonfiction comics from the start?

I had a penchant for editorial and political cartooning. When I applied to SCAD I put in my letter that that was something I was interested in doing. I remember when the Pulse nightclub shooting happened. I was in Mexico at the time and there was something about this major event happening in the US, and I wasn’t in the US. Not that I could have done anything if I was in New Jersey, but I needed to do something and so I drew a visual essay about my feelings and how the country was handling it and it felt great. From there I moved into doing work for The Nib, The Boston Globe, and a few other more journalistic outlets and it became my niche. Which is not to say that I don’t make goofy comics about cats now and then. I still make fiction comics but in terms of “day jobs” comics, I do nonfiction work or historical based retellings.

Did comics become the way you were able to process and think about events?

Definitely. The shooting happened and I didn’t know what else to do with myself, so I drew the comic. People started reading them and got something out of it and it wasn’t just me personally working through things. It definitely motivates me to keep making that kind of work.

I thought about that in terms of some of your other work. For example on The Nib you had a piece this year on COVID myths and that felt like you taking in all this information and trying to make something and do something.

That one in particular. When all of this covid stuff started and you had that daily realization of, oh, we’re living in a fantasy/horror movie. I’m an artist and so I couldn’t start helping people on the front lines. I had days of going, what can I do to help? What am I doing with my life? Who is this helping? So when The Nib reached out to me to do that, I said, yes! This is what I needed. When we did that comic the general acceptance was we don’t need masks. So we had to go back and change that.

I remember that distinctly because it came out in March.

And so much changed after that! New Jersey shut down March 15, I think, but on March 10 I went to a hockey game! Literally the last New Jersey Devils game before sports stopped. It changed so fast.

You also had a great piece on The Nib over the summer about the Suffrage movement and how that intersected with the 1918-19 pandemic, which was really great.

Another project I worked on recently was an anthology that I edited about the 19th Amendment, so I was super plugged into all things suffrage. This year is the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the amendment, so when this went down I remember a New York Times article about the connection between them. To see what they went through – and they had much higher stakes. That was another thing that helped me cope. I’m glad that The Nib let me do that. The end result was that persisted and they didn’t let the pandemic stop them. The moral was, this stinks, but we can’t let it stop us from doing the things we have to do. Super relevant with everything happening with the protests and Black Lives Matter. There are huge parallels to what’s going on today.

So how did you end top drawing Fault Lines in the Constitution?

Mark Siegel came to me with the book and said we’re doing this new line of comics – they didn’t even have a name for it yet – but he said, we think you would be a good fit. I thought it sounded cool and they sent me a copy of the original book by the Levinsons. I read it in a day, and said, yes, I’m in. I basically took the original book, turned that into a script and made it into a comic. It sounds so silly to say it that way.

So you had to adapt the book and draw it. What kind of timeframe did you have to do all that?

From the time we worked out the administrative details to me turning in the final artwork, was about a year. It was an intense year. My partner also does comics so he did the coloring. The editorial staff at First Second was a really big help in keeping things moving. They are very trusting of their artists and flexible in working with the way I worked. At some point a newer version of the original Fault Lines book came out with two new chapters, so we had to reconfigure the schedule to fit two more chapters into the book. That was my year. All Fault Lines, all the time.

I’m sure that was exhausting and overwhelming, but also exciting because you’d been working towards a point where someone says, here’s this hugely ambitious project, we trust you, go.

Of course! It felt great. And anytime I had this moments of, “why did they ask me?” Mark would always hop on the phone with me and talk me off the ledge. Samia Fakih, one of the editorial assistants who worked on the book, was fantastic. Especially in the final rounds of edits, she was so on top of fine tuning the book. She made some suggestions that at the time I went, okay, fine, but now if she hadn’t suggested it, it made such a huge difference. They were all very very supportive.

As far as scripting process, did you start with the book, keep the chapters and structure and convert it?

That was the starting point, but any adaptation is not a one to one translation. Nor should it be. Some things had to change. There are things in there where there’s no real visual way to tell it and keep the pacing. That’s why there are portions of chapters that are more like visual essays rather than comics pages. I had to mess around with the comics and I had to change some things from the original book. Reading the original book I had a template. In each chapter they talked about the overall topic, introduced a case study and usually a more modern day case study, then brought it back to the Constitutional Convention and what the framers were talking about. Then bring in International examples or state level examples and tie it back to the beginning. I kept that but then there were these little asides that were tangentially related. In some cases I had to decide, can I fit it in? Will it break up the sense of pacing and structure if I do? I had sticky notes about, I need to mention this, where will that fit in? It was a long process, but it needed that. And it deserved that. There was so much material that you didn’t want to take out to be easier.

Reading the original book, the Levinsons clearly did a lot of research. How much research did you have to do to get to the point where you felt comfortable enough to start drawing this?

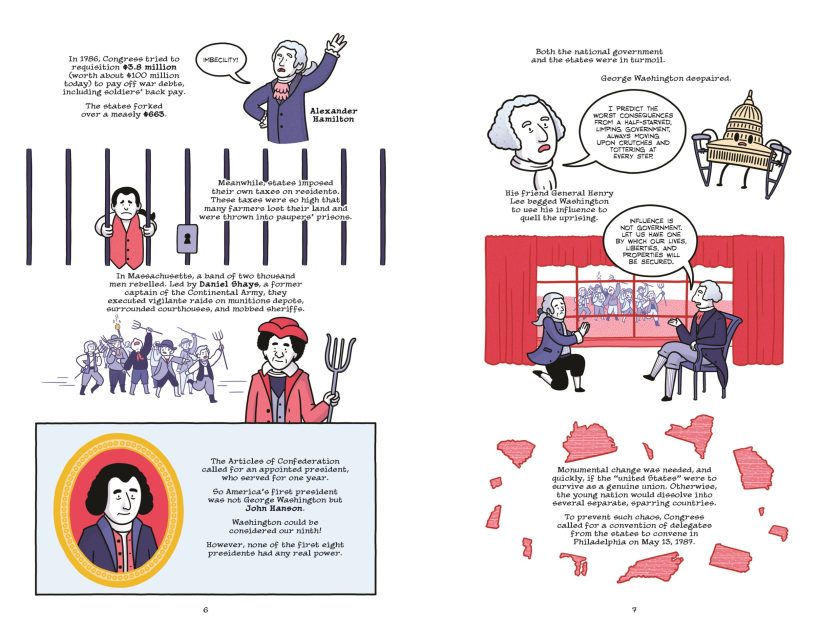

A lot of visual research, that’s for sure. I mean you can see what the Founding Fathers looked like but to get to the point where you’re drawing all of them over and over of them. You have to figure out many different ways to portray Constitution Hall. I can’t just have the same angle. It took a lot of visual reference and research. The original book gave me the knowledge base to do it. They didn’t leave any major gaps where I felt like I needed to read additional books. Of course because I’m a nerd I found a podcast on the Constitution – but in terms of the actual material, it was more that I had to do my job of figuring out what people were wearing, what did clothes look like, what did the streets look like. Not that I draw hyper realistically where I had to get every single detail right, but you have to figure out, were women’s dresses ankle length or to the floor? Would he have been wearing a top hat or bowler hat?

And I’m sure at a certain point, you’re only researching what you need and you don’t have time or energy for anything more.

Yeah and it’s so easy to fall down rabbit holes that are unhelpful. That’s something I tried to keep in mind. The whole point of this book isn’t to write a textbook. If I didn’t draw the exact number of windows that the White House has, that’s not going to change the readers’ experience. The book isn’t to teach them how many windows the White House has. As much as you might want to be a perfectionist, you have to temper that.

Also if you’re drawing it, the White House is being pictured for a reason and if people recognize and understand that, your job is done.

Again, that’s the point of being the artist on something like this. Really what we’re doing is drawing symbols for people to recognize. It’s not a photograph of George Washington. I’m drawing a symbol so that when people look it, they recognize it to be George Washington.

You mentioned before about how you were a teacher when you were younger, how much do you think that experience influenced how you put this book together?

Quite a bit. I’ve taught on the high school and college level at this point and that informs so much – how you talk to people, and the editing that I’ve done, how I word my notes to other artists. The knowledge of people’s different learning styles and how people interpret information. Whenever I’ll do a page layout, it’s definitely in my subconscious that someone might not read it that way or maybe this balloon order won’t be how people read it. It’s infused into all levels of this. Because at the end of the day, these are didactic comics. They’re there to teach people. Not to say that if someone has no teaching experience that they couldn’t make an amazing comic, but it helps to be aware of the ways that people learn and would approach material like this.

As you’re putting this together, you’re consciously and not, finding multiple ways to explain or guide people through the material.

Definitely. That also came into play when thinking about how there’s the original book and they’re not going to stop printing it because there’s the graphic novel version. Once I accepted that, and that the comic version is different from the original, that allowed me to not cling too tightly to the original script of the book. That goes back to multiple ways of reading because some people will be more comfortable and get more out of the original prose book and others will be more comfortable and get more out of the comic version. Having this options for readers – especially middle grade readers – is huge.

I’m curious about your conversations with First Second about the approach and design of the book and how it should look.

In terms of how I approached the original book, they basically said, here’s the book. One of the things Mark said was, you have a good way of taking bigger, heavier material and putting it into a more palatable digestible terms in your comics. You can take this huge topic and turn into a twenty panel comic and not be just full of words. He basically said, we trust you to take this book and turn it into a comic. Comics work well when they’re a good balance of words and pictures. I approached it the way I approach most of my nonfiction comics, which is finding a good balance of letting the visuals speak when they can and using the words when you need to. Shoutout to Eleri Harris at The Nib, because she’s been a huge, huge influence in teaching me when not to use words. I think I tended to be very reliant on words and not letting the visuals do the heavy lifting. But working on The Nib really taught me to trust the pictures. I was able to go through the original book and go, where can I use a picture? Where can I reduce the words to only what’s necessary? The writers got brought in to do edits and would say things like, we included the entire wording on this in the book. Well, that works great in the book, but it’s not great for comics. Already it’s a very text-heavy comic because it has to be. It would be doing the reader a disservice to not. For the graphic novel version, do we need the entire text of the Constitution in there? When I said, maybe we should change this from the original, Mark and everyone else at First Second was very supportive.

I felt like the character work in this book versus some of your other work was simpler and more open in terms of the character design.

Yes. Also there are a lot of real people in the book and I also had to make up a lot of characters. I didn’t want a super hyper realistic George Washington and then a generic random girl character. So I had to find a style where it all blurs together so you can recognize that that’s George Washington but he doesn’t look super different from these background characters.

That’s the kind of approach that because it looks easy to draw – and is easy to read – some people think its easy to make, but it’s really not.

It’s not! That’s something I’ve been trying to do in my work, simplify things. I’m working on another book for the World Citizen Comics line that hasn’t been announced yet and all of the so many times I had to draw the White House and the Capital, I look at it now and go, I drew so much detail! I’ve been trying to cut back even more and figure out when you need the detail and when you don’t. I’m trying to be smarter with that, but it takes time. Because I’m not being lazy just drawing it this way, it’s to make a better panel. If the background isn’t crazy busy, it will read better. It’s tough to find that balance, but it’s also fun. It’s like a puzzle. What can I do so it looks like it’s supposed to?

I wanted to ask about coloring, which works really well with the style you chose.

My husband, Gerardo Alba, did the coloring. We went through a couple different palettes. When we did the sample pages to get the initial approvals we did a full color palette and for the sample and it looked really good, but the more we thought about it, there was too much going on in the book. In my perfect world I would do all my comics in all black in white, but in a lot of the stuff I do I keep to a limited color palette. My simple style lends itself well to a limited color palette. We leaned towards red, white and blue. But some things needed to stand out. We had flags and we had to color those accurately. So we used other colors, but only for good reasons.

So you were at one end of the table drawing and he was sitting at the other end coloring?

I would go, here’s another page! It was all digital, so it wasn’t really like that, but in my mind it was. [laughs] That was really helpful too because if he had a question he could just turn around and ask. It’s nice to share a studio space sometimes. And as much as I said I love black and white comics before, the color really transforms the work.

Tell me about Little Red Bird Press.

It’s my and my partner Gerardo’s publishing company. We met at SCAD. We both make comics. When we both graduated we saw a lot of people were turning to Kickstarter and we started spending out pitches, but we wanted to make comics so we collaborated on a short graphic novel, put it up on kickstarter and it got funded. We used Little Red Bird to publish the things we want to publish. We’ve had a few Kickstarters and our most recent one was Votes for Women. Over 30 women artist worked on the book about the 19th Amendment, from the original British suffragettes to the ERA today. It was on Kickstarter in March and it was finally published last month.

Not that it’s not completely relevant to what’s happening right now, but I’m sure it was nice to have a different kind of project.

Definitely. Working on Fault Lines or the book I’m working on now about democracy and different types of governments, there are moments where it’s heavy and it can be depressing. Especially when everything is going on in the world and you look around our country. As you were saying before, when you work on a book like this for over a year, it’s so easy to be consumed by it. It’s good to break out of it a little bit. It’s the curse but also the blessing of working on something that’s so relevant.