It’s Blackout Tuesday, and we’re centering Black creators with a short list of comics and graphic novels that explore issues of police brutality, the experiences of Black people, and how to work toward structural change. To find more Black creators, follow the #drawingwhileblack hashtag on Twitter and check out Sheena Howard’s Encyclopedia of Black Comics (full disclosure: I was a contributor).

Read. Learn. Then go out and change the world.

APB: Artists against Police Brutality, edited by Bill Campbell, Jason Rodriguez and John Jennings: Published five years ago, this collection of comics, prose and poetry looks at the problem from the point of view of people of color, chronicling the sorrow of lives lost and the anxiety of knowing that at any moment, peace may turn to bloodshed. Powerful and still very relevant. This book is available on ComiXology and directly from Rosarium, which is a black-owned publisher of science fiction and graphic novels that is well worth checking out.

They Shoot Black People, Don’t They? by Keith Knight: Knight collects 20 years’ worth of comics about police brutality in this slim volume, regarding the topic with a sharp pen and wry humor. The book distills a slide show he gives around the country, with some extra cartoons added in. Check out his up-to-the-minute comics on his website, where you can also pick up print editions of his books, and throw him some support on Patreon as well.

March, by Rep. John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell: Lewis’s three-volume memoir of the Civil Rights movement, starting with the desegregation of the Nashville lunch counters and culminating with the passage of the Voting Rights Act, can be read as a handbook for change. The authors depict the careful planning that went into protests, the arguments that often occurred behind the scenes, and the way each action played out. It’s a compelling story in its own right, but it’s also a valuable document for those who are looking forward as well as back.

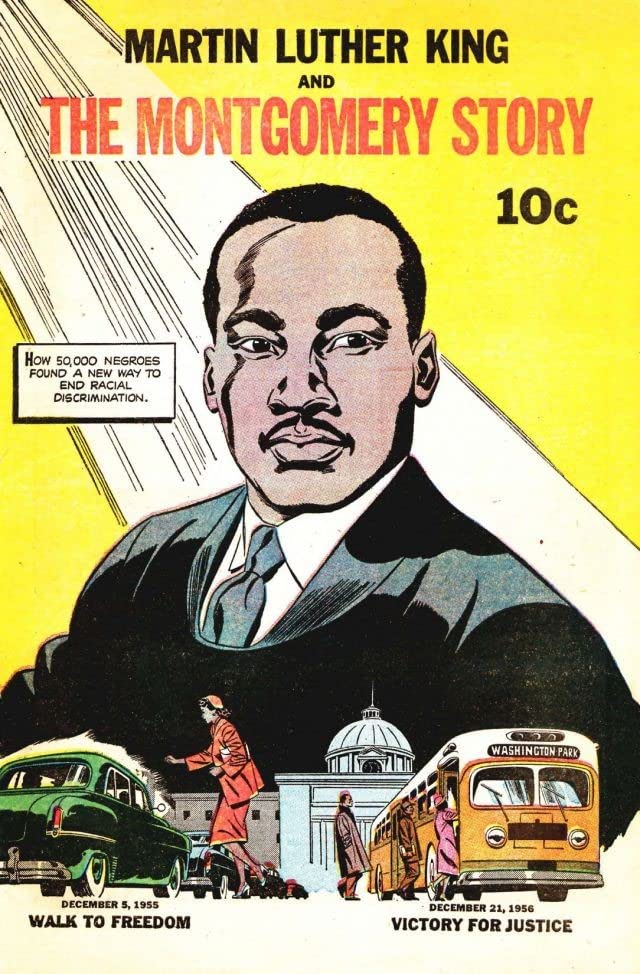

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, by Alfred Hassler, Benton Resnik, and Sy Barry: If you’re looking for a literal handbook for protest, this 16-page comic book, published and widely distributed by the Fellowship of Reconciliation beginning in 1957, lays out the dos and don’ts in simple terms. The comic is available digitally at ComiXology for $1.99 and as a hard copy from the Fellowship of Reconciliation for $5.00 (there are discounts for bulk orders, and it is available in Spanish, Arabic, and Farsi as well as English). This comic book was one of the inspirations for March.

New Kid, by Jerry Craft: Jordan Banks wants to be an artist, but his parents insist that he attend a fancy prep school with a predominantly white student body. Craft has an excellent eye and ear for the small incidents that build up over time, as Jordan negotiates the two very different worlds of his neighborhood and his school. This is a middle-grade graphic novel, but the writing is sharp and witty and it’s a good read for adults as well.

Your Black Friend, by Ben Passmore: White readers may cringe as they read Passmore’s 12-page minicomic, which won the Ignatz Award for Outstanding Comic in 2017, but the comic isn’t about you, it’s about him, the Black friend, and the confusion and dislocation he feels in a world filled with good intentions, misapprehensions, and contradictions. This is one to read over and over. You can read it for free on the Silver Sprocket site and buy your own copy for a mere $5.

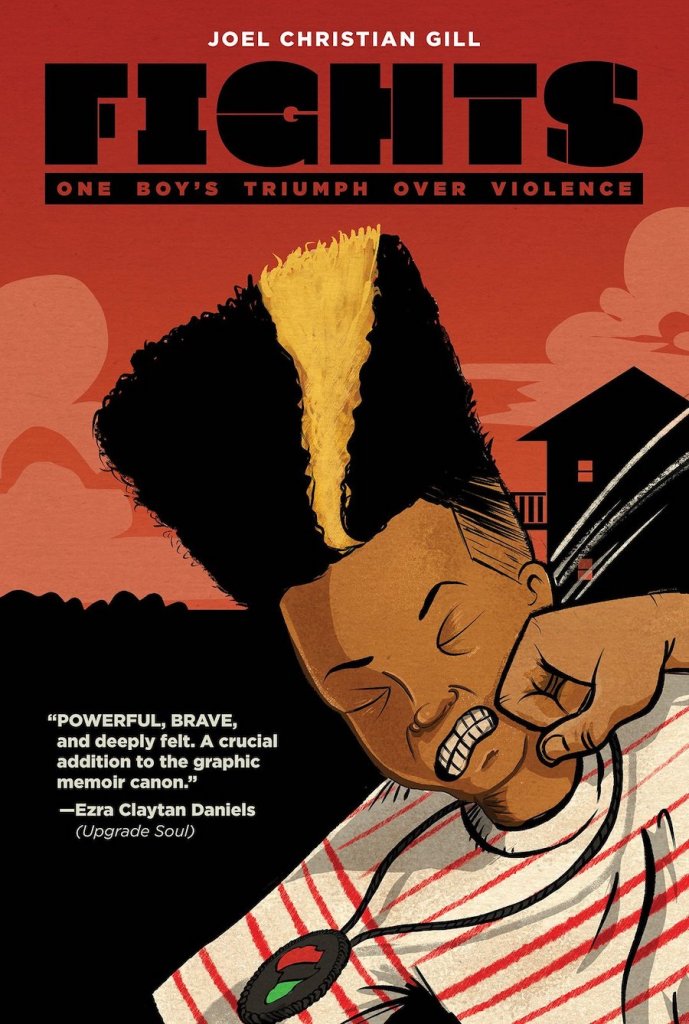

Fights, by Joel Christian Gill: Gill’s comic is an unsparing account of his experiences as a child and teenager, a chronicle of violence and sexual abuse that somehow ends up being hopeful at the end. For those who want to walk a mile in another’s shoes, this is a good start.

Kindred, by Octavia Butler, adapted by Damian Duffy and John Jennings: Jennings’ electric line adds an immersive aspect to Butler’s tale of a Black woman who travels back in time from the present (1967) to the 19th century, a time when she is presumed to be a slave – and her white husband, when he travels back with her, must pose as her owner. The book forces the reader to confront the cruelty and twisted logic of slavery in a very concrete way.